The Hawaiian monk seal, Neomanachus schauinslandi, is one of the most endangered marine mammals in the world and the most rare of the pinniped family (seals, sea lions and walrus) in the western hemisphere.

It is believed that the animal is named “monk” seal due to its solitary lifestyle as well as folds of skin on its neck that some believe resemble a priest’s cowl. These animals can live in the range of 30-35 years (usually less in the wild) and spend about 1/3 of their time on land. They are benthic foragers (bottom feeders) and have been observed swimming at depths greater than 1,800 feet though their normal range of activity is less than about 300 feet. They can stay under water for up to 20 minutes and divers report seeing them napping under water. Adult animals are 6 to 8 feet long and can weigh between 350 and 500 pounds or more.

The Hawaiian monk seal is the only tropical seal species left in the world and only lives in Hawaiian waters. Its closest relative, the Caribbean monk seal is extinct. Living in Hawaiian waters for millions of years, before some of the islands were even fully formed, these animals were undisturbed for thousands of generations before human settlers in the middle ages and seal hunters in the 19th century hunted and killed these animals to near extinction. Later, in the 20th century their numbers were further impacted by the build-up of human presence, environmental damage, and ecosystem changes within the Hawaiian archipelago. Today, there are barely 1,600 of these animals left in the world, about 1,200-1,300 of which live around uninhabited islets and atolls in the northwestern Hawaiian island chain, with only about 300-400 animals living around the main Hawaiian Islands of Niʻihau, Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, Molokai, Maui, Lānaʻi, Kahoʻolawe and Hawaiʻi Island.

The small but stable population of animals living around the main Hawaiian Islands provides an important hope for the survival and ultimate recovery of the Hawaiian monk seal species but these animals are threatened by fishery interactions (hookings, entanglement in nets, etc.), human-caused trauma and toxoplasmosis (a disease carried by outdoor cats).

This iconic and charismatic species, called “a living fossil” by scientists, has suffered these dramatic population losses and the threats of extinction due to impacts largely caused by one species – man. And it is up to one species – man, to help the Hawaiian monk seal survive and recover.

The Hawaiian monk seal is an apex predator and a sentinel species. Its beach is our beach. Its waters are our waters. It eats some of the same food we eat. As a sentinel species, the fate of the Hawaiian monk seal may foretell our own. Its success is our success.

The monk seal is known in Hawaiian as Ilio-holo-i-ka-uaua, which means “dog running in the rough seas,” or na mea hulu, which means “the furry one.”

Did You Know?

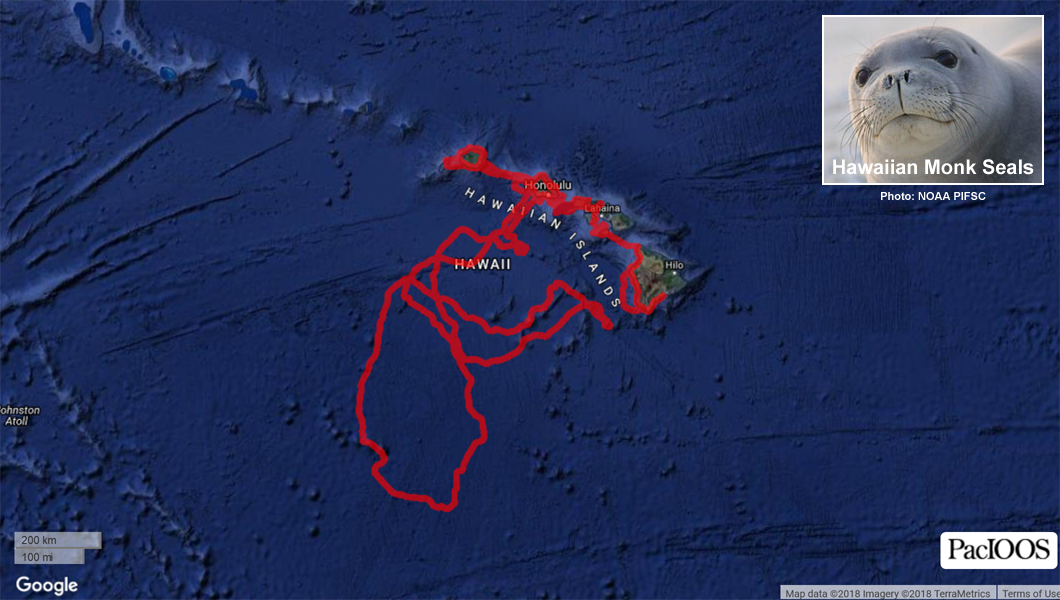

Monk seals do not migrate seasonally, but some seals have been tracked traveling hundreds of miles in the open ocean.

The image to left shows the satellite tracking of a Hawaiian monk seal.

Sharing the Environment with Hawaiian Monk Seals

If you are fortunate enough to see a seal on the beach or in the water in Hawaii, please remember to give these animals some space for your safety and their stewardship. The small Hawaiian monk seal population in the main Hawaiian Islands is currently stable and we are lucky to have the opportunity to view monk seals.

It is not uncommon to share the beach with a monk seal. However, it is a privilege that comes with responsibilities. Responsible wildlife viewing helps to ensure your safety and the animals’ long-term survival in the wild.

Marine animals such as monk seals, sea turtles, dolphins and whales are part of the identity of our islands and hold a special place in the minds and hearts of the many people in Hawaiʻi. While viewing marine animals, you should ensure that your actions do not disturb the animals you are observing.

Help preserve the Hawaiian monk seal, let sleeping seals lie.

If no HMAR, law enforcement or NOAA-authorized personnel are on scene it is recommended you stay 50 feet from monk seals, 150 feet if you encounter a monk seal mom with a pup.

If a seal approaches you, move away to avoid interaction. If you are in the ocean, move away from the animal or cautiously exit the water if possible.

Pets, especially dogs, can pose a risk to monk seals. Please keep dogs on leash when in the presence of monk seals to avoid injury or disease transmission for both seals and pets.

It is natural for monk seals to come ashore or “haul out” on the beach for long periods of time. Please give them space so they may rest, molt, give birth and rear their pups. Do not attempt to push them back into the water, pour water on them or wake them up by approaching too closely.

Roped off areas or signs that have been placed on the beach by Hawaiʻi Marine Animal Response (HMAR) or other authorized personnel are there for your safety and to minimize animal disturbance so please stay behind any ropes or signs. If HMAR, law enforcement or other NOAA-authorized personnel are on scene (identifiable by uniform or ID), please follow their recommendations and instructions for safe and responsible viewing.

Cautiously move away if you observe the following monk seal behaviors indicating it has been disturbed:

- Female attempting to shield a pup with her body or by her movements.

- Vocalization (growling) or rapid movement away from the disturbance.

- Sudden awakening from sleep on the beach.

Review NOAA’s Fisheries Interactions Guidelines: Download

In the ocean, monk seals may exhibit inquisitive behavior. Approaching or attempting to play or swim with them may alter their behavior and their ability to fend for themselves in the wild. In addition, a monk seal “playing” with a human can inadvertently cause injuries or even death to the human.