Rare Birds News

Rare Birds Could Be Making Oahu Home Once Again

Rare Birds Could Be Making Oahu Home Once Again

by Christine Tarski

Hundreds of years ago, the Newell's Shearwater, ‘a’o, were abundant, thriving, and flying over the waters surrounding all the main Hawaiian Islands. Uncovered fossils show that large colonies of these birds were established in the middle and higher levels of highly vegetated mountain peaks. Native Hawaiians hunted the birds extensively on Oahu to the point that there were no remaining birds left in the beginning of the 1800’s when Europeans began moving to the islands. With the introduction of invasive owls, cats, mongoose, pigs, and rats on other islands, the ‘a’o population was further decreased.

Although they were once believed extinct, important new research suggests ‘a’o may be living and breeding on Oahu. Established as a new species in 1900, the ‘a’o were sadly declared extinct in 1908, but were amazingly rediscovered at sea in 1947. Biologists were thrilled to find breeding pairs on Kaua’i in 1967. In the 1990’s, ‘a’o’ numbers were estimated at 20,000 breeding pairs. ‘A’o’s are nocturnal and make nesting areas by burrowing into sheer mountain cliffs covered with dense vegetation. These two facts made studying the remaining birds very difficult.

We know that ‘a’o’s lay a single egg around June, which is incubated by both parents. Once the chick hatches, both parents continue to care for and feed the chick collaboratively. Parents may fly hundreds of miles and return at night to feed the chick. By November, the chick fledges and is on its own.

In the fall of 1992, Hurricane Iniki wiped out many of the chicks who were close to fledging. Further decrease in the population of these seabirds has resulted from predators, light pollution, collision with power lines/wind turbines, habitat loss, and possible disease.

‘A’o’s are now considered classified as threatened by both state and federal governments. Breeding colonies are mainly on Kaua’i, with smaller colonies on Hawai’i, Lehua and Molokai. ‘A’o’s have been seen on other islands occasionally, including Oahu, but were considered birds that were thrown off course by storms or confused by city light pollution.

Since the 1990’s, numerous groups have been working to implement conservation measures. These measures include hooding all street lights on Kaua’i and reducing resort lighting, initiating and increasing predator controls, and establishing native plant life in nesting areas.

For the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) recovery action planning, Pacific Rim Conservation’s Lindsay Young conducted a statewide survey of several seabirds, including ‘a’o’s, during 2016-2017. Her team used acoustic recorders, putting the devices in very remote high mountainous areas, sometimes using helicopters, sometimes climbing and scaling dangerously steep crags. Although Oahu was not included in the islands to survey, Young, who lives on Oahu, decided to place recorders in 15 places on this island.

Her team was very excited to hear calls of the ‘a’o over the two years of recording. ‘A’o were heard at two places on Oahu: one was on the leeward slopes of Mount Kaala in the Waianae Mountains and another at Poamoho in the Koolau Mountains.

Although there could be nesting colonies on Oahu, Young feels these also could be “young birds from other islands that are searching for mates and breeding sites. Either way, it gives us hope that we will be able to … attract them to nest on an island where they were once abundant.”

So, how do you and I recognize these once extinct birds? ‘A’o or Newell’s Shearwater are highly pelagic (on the open ocean) throughout the year. From April through November, ‘a’o’s can be seen in the Hawaiian Islands. The rest of the year, they take to the tropical ocean, as far west as the Mariana Islands and as south as Samoa. They are 13” in length with a wingspan of 8.8 - 9.8”. Both male and females are a very dark brown above with a white throat and underparts. Their bill is also dark with a hooked tip while the legs and feet are pink. When seen flying, these birds fly fast and low over the water with rapid wing beats and fewer glides.

‘A’o’s will dive into the ocean and actually swim down to 30’ with their wings partially folded to catch their prey. They gather with other seabirds and look for schools of tuna. The tuna drive smaller fish and squid to the surface where the ‘a’o’s happily feed. Their call, usually only heard in nesting areas, sounds like a donkey braying.

As well as watching the ocean for seals, sea turtles, whales and dolphins, be sure to also look up to the sky, and keep your binoculars ready. You could very well spot an ‘a’o for yourself.

Hawaii Marine Animal Response (HMAR) is a first responder for Hawaiian monk seals and sea turtles on Oahu and we also handle rescues and transport for seabirds that may need assistance. If you see a seabird that may need help, please call our hotline at (808) 687-7900. If you see a marine mammal or sea turtle of concern, please call us (888) 256-9840. Learn more about HMAR, Hawaii’s protected marine animals and how you can help HERE.

Corporate Sponsor Programs

Hawai’i Marine Animal Response (HMAR) Corporate Sponsorship Programs

It takes a lot to run our field outreach, rescue, education, marine debris, and stranding response programs. We work hard to cover our costs through grants and private donations, but we still need help. We’re looking for business partners and sponsors to support our ongoing work and help us make an even bigger impact on the protected marine animals and the ocean ecosystem we all love. Whether your organization shares a beach with resting monk seals or your guests come back year after year to enjoy seeing sea turtles and seabirds, this is an opportunity to directly support the conservation of these important animals.

It takes a lot to run our field outreach, rescue, education, marine debris, and stranding response programs. We work hard to cover our costs through grants and private donations, but we still need help. We’re looking for business partners and sponsors to support our ongoing work and help us make an even bigger impact on the protected marine animals and the ocean ecosystem we all love. Whether your organization shares a beach with resting monk seals or your guests come back year after year to enjoy seeing sea turtles and seabirds, this is an opportunity to directly support the conservation of these important animals.

Your organization or business can play an important role in helping HMAR in our mission of helping Hawai’i’s protected marine animals and our shared ocean ecosystem. We offer several different sponsorship programs, or we can customize a program especially for you. HMAR sponsorships begin with a minimum annual donation of $1,000 or more in cash or in-kind donations. Donations can be made in a single transaction or provided through an easy monthly or quarterly installment plan.

Sponsorship benefits include:

- Positive community awareness of your proactive preservation and stewardship efforts.

- Employee participation in HMAR conservation efforts.

- A package of exclusive, high-value rewards that include brand alignment and media exposure.

Interested in becoming a Sponsor?

Below you’ll find an outline of the different packages we offer to supporting organizations who support HMAR annually at various levels. Your contribution can be financial, in-kind, or a combination of both. You can choose one of the programs below or we can customize a program for you based on your interests, financial commitment level and other factors. Please take the next step in becoming a HMAR sponsor by sending us an email by clicking HERE.

Platinum Level Sponsor

Platinum Level Sponsor

This sponsorship level is tied to a commitment to provide financial and/or in-kind sponsorship at a minimum of $50,000 per year. The Platinum Level Sponsorship includes:

- Line of business exclusivity with right to veto competitors who are prospective Platinum, Gold, or Silver sponsors.

- Press Release, Facebook and Instagram announcement.

- License to use HMAR logo for use on web, marketing and other promotional materials.

- License to use selected HMAR images and videos for events or social media posts.

- Name and logo recognition positioning on HMAR “Platinum Sponsors” webpage with live link to the sponsor’s URL.

- Framed and signed artist print for a location of your choice.

- HMAR website footer logo recognition.

- Placement on HMAR supporters page with live link to sponsor’s URL.

- Sponsor logo at the end of HMAR videos.

- Sponsor logo recognition/signage at HMAR field response locations (subject to response conditions).

- Sponsor logo placement at outreach tables at community and school events.

- Placement on HMAR Facebook Page on cover image

- Name and logo placement in HMAR email newsletter.

- Name and logo placement on HMAR staff email signatures.

- Name and logo placement on HMAR staff business cards and letterhead.

- Name and logo placement in public advertising and awareness campaigns, including banners and flyers.

- Up to 2 of your team members can participate in a “ride-along” with HMAR field response staff during a 4-hour shift. (This is a great employee recognition gift.)

- Planning and execution of two activities for up to 50 sponsor staff and/or sponsor invitees (coordination and planning is covered, but hard costs apply for transport/food), such as:

- “Pup Prep” cleanup on beaches where monk seals typically give birth

- “VIP Pup Picnic” at a safe distance from a new pup and mom

- Mural painting party with local artist (subject to availability of appropriate wall)

- Opportunity to provide sponsor marketing materials, run competitions, or provide giveaways at events.

- Opportunity to provide co-branded merchandise for our team members to wear during media appearances, beach cleanups, and education/outreach events (hats, reusable water bottles, T-shirts, etc.).

- Additional partnership opportunities possible.

Gold Level Sponsor

Gold Level Sponsor

This sponsorship level is tied to a commitment to provide financial and/or in-kind sponsorship at a minimum of $25,000 per year. The Gold Level Sponsorship includes:

- Press Release, Facebook and Instagram announcement.

- License to use HMAR logo for use on web, marketing and other promotional materials.

- License to use selected images and videos for events or social media posts

- License to use selected HMAR images and videos for events or social media posts.

- Name and logo recognition positioning on HMAR “Gold Sponsors” webpage with live link to the sponsor’s URL.

- Framed and signed artist print for location of your choice.

- HMAR website footer logo recognition.

- Placement on HMAR supporters page with live link to sponsor’s URL.

- Logo at the end of HMAR videos.

- Logo recognition/signage at HMAR field response locations (subject to response and other conditions).

- All the benefits of the Hawai’i Marine Stewards program (see below) and up to 2 Hawai’i Marine Stewards annual employee training events.

- Up to 2 of your team members can participate in a “ride-along” with HMAR field response staff during a 4-hour shift. (This is a great employee recognition gift.)

- Planning and execution of two activities for up to 25 sponsor staff and/or sponsor invitees (coordination and planning covered, but hard costs apply for transport/food), such as:

- “Pup Prep” cleanup on beaches where monk seals typically give birth

- “VIP Pup Picnic” at a safe distance from a new pup and mom

- Mural painting party with local artist (subject to availability of appropriate wall)

- Opportunity to provide marketing materials, run competitions, or provide giveaways at events.

- Further opportunities to be discussed.

Silver Level Sponsor

Silver Level Sponsor

This sponsorship level is tied to a commitment to provide financial and/or in-kind sponsorship at a minimum of $10,000 per year. The Silver Level Sponsorship includes:

- Press Release, Facebook and Instagram announcement.

- License to use HMAR logo for use on web, marketing and other promotional materials.

- License to use selected images and videos for events or social media posts

- License to use selected HMAR images and videos for events or social media posts.

- Name and logo recognition positioning on HMAR “Silver Sponsors” webpage with live link to the sponsor’s URL.

- Framed and signed artist print for location of your choice.

- Supporters page with live link to specified URL.

- Logo at the end of selected HMAR videos.

- Up to 2 of your team members can participate in a “ride-along” with HMAR field response staff during a 4-hour shift. (This is a great employee recognition gift.)

Supporter Level Sponsor

Supporter Level Sponsor

This sponsorship level is tied to a commitment to provide financial and/or in-kind sponsorship of a minimum of $1,000 per year. The Supporter Level Sponsorship includes:

- Press Release, Facebook and Instagram announcement.

- License to use HMAR logo for use on web, marketing and other promotional materials.

- License to use selected images and videos for events or social media posts

- Name and logo recognition positioning on HMAR “Supporters” webpage with live link to the sponsor’s specified URL.

- Up to 2 of your team members can participate in a “ride-along” with HMAR field response staff during a 4-hour shift. (This is a great employee recognition gift.)

Won’t your organization help us to continue and to expand our important work? If you can, please email us by clicking HERE.

Mahalo for your support!

How To Tell The Difference Between a Green and Hawksbill Sea Turtle

|

Common name: Green Sea Turtle Hawaiian name: Honu Latin name: Chelonia mydas Status: Protected & Threatened |

|

Common name: Hawksbill Turtle Hawaiian name: ‘Ea Latin name: Eretmochelys imbricata Status: Protected & Endangered |

Comparison of the Green turtle and the Hawksbill turtle:

|

Green Turtle

|

Hawksbill Turtle

|

|

|

Hawaiian Name

|

Honu

|

‘Ea

|

|

Status

|

Threatened

|

Endangered

|

|

Distribution

|

Common

|

Not common, mostly Maui and Big Island

|

|

Adult Weight

|

Up to 500 lbs.

|

Up to 200 lbs.

|

|

Adult Shell Length

|

3-4 ft.

|

2-3 ft.

|

|

Diving Depth

|

Up to 1500 ft.

|

Up to 1500 ft.

|

|

Breathing Cycle

|

Resting up to 3 hours

Normal – every 15 to 30 mins.

|

Up to 3 hours

Normal – every 15 to 30 mins.

|

|

Diet

|

Limu, seagrass and invertebrates

|

Sponges, algae & invertebrates

|

|

Sexual Maturity

|

25-35 years

|

20-29 years

|

|

Lifespan

|

80-100 years

|

30-50 years

|

|

Hawaii Nesting Activity

|

500-800 per year

|

20-25 per year

|

|

Basking

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Carapace (Shell)

|

High domed

Non-overlapping scutes

Smooth edge

Olive to black color

|

Flatter, more colorful

Overlapping scutes

Jagged edge

More colorful

|

|

Claws

|

1 per flipper

|

2 per flipper

|

|

Nesting Frequency

|

2 to 8 years

|

4 years

|

|

Intervals of Nesting

|

4 nests / 14 days apart

|

1 to 6 nests / 20 days apart

|

|

Eggs/Clutch & Incubation

|

~100 eggs / ~2 months

|

~180 eggs / ~2 months

|

Frequently Asked Questions ( FAQ )

Q. There’s a monk seal on the beach and it looks sick – what should I do?

Q. There’s a monk seal on the beach and it looks sick – what should I do?

A. Most seals that haul-out on the shoreline are just fine. They may have mucus around their eyes, scars on their body, and may lie very still, as if they are not breathing, but that’s normal. Please keep your distance; do not try to get close to the animal. Please stay behind any signs or ropes erected by Hawaii Marine Animal Response (HMAR) or other authorized personnel. If there are HMAR, law enforcement or other NOAA-sanctioned personnel on scene (identifiable by uniform or ID), please follow their instructions and recommendations for safe and responsible viewing. Hawaiian monk seals need to be allowed to rest undisturbed. Please report all sightings of monk seals by calling our 24-hour toll-free hotline at 1-888-256-9840.

Q. There’s a whale or dolphin on the beach or swimming in very shallow water – what should I do?

A. Whales and dolphins on the shoreline or swimming in very shallow water (less than 5 feet) are usually sick or injured. Please keep your distance – these animals are very strong, heavy, and unpredictable – and call our 24-hour toll-free hotline at 1-888-256-9840.

Q. I see a marine mammal that’s entangled in string, rope or net – what should I do?

A. Call the 24-hour toll-free hotline at 1-888-256-9840. If it’s safe, please stay nearby the animal to keep track of it until trained responders can arrive. Never try to untangle a marine mammal on your own, without permission and guidance from NOAA. Too many well-meaning people have been seriously injured or drowned while attempting to save an entangled whale, dolphin or seal.

Q. What should I do if I accidentally hook a monk seal while fishing or if I see a hooked seal?

A. Please immediately call our 24-hour toll-free hotline at 1-888-256-9840. You may make your report anonymously. You will then be given guidance over the phone on what to do depending on the situation. Review NOAA’s fisheries interactions guidelines for more information on how to avoid seal interactions.

Q. Why should we protect Hawaiian monk seals? They don’t belong in the main Hawaiian Islands and eat all our fish!

A. Hawaiian monk seals are native to the Hawaiian Islands, and occur nowhere else in the world. See Hawaiian Monk Seal Myths and Facts. There is good archaeological evidence that monk seals were here before the first humans arrived in the Hawaiian Islands. Seals usually feed on bottom-dwelling creatures, such as eels, flatfish, wrasses, octopus, and crustaceans. Seals have never been observed hunting pelagic fish, such as mahi-mahi, ahi, aku, etc. Like sharks and other marine predators, seals play an essential role in our reef ecosystem, maintaining a balance that allows for the highest levels of productivity in our local fisheries.

Q. How close can I get to monk seals?

A. There is no law specifying the minimum distance people can approach a monk seal, however, getting close to these animals may constitute a violation of federal or state law if the animal is disturbed or if your action has the potential to intentionally disturb its natural behavior. If Hawaii Marine Animal Response (HMAR), law enforcement or other NOAA-sanctioned personnel are on scene (identifiable by uniform or ID), please follow their instructions and recommendations for safe and responsible viewing. Please stay behind any signs or ropes that have been erected by HMAR or other authorized personnel. They are there for your safety, to minimize animal interaction and for your awareness. If no signs, ropes or authorized personnel are in the vicinity, it is recommended that you stay at least 50 feet from Hawaiian monk seals and 150 feet if you encounter a mother monk seal with a pup. Pets, especially dogs, can pose a risk to monk seals. Please keep them on a leash when in the presence of monk seals to avoid injury or disease transmission for both seals and pets. In the ocean, monk seals may exhibit inquisitive behavior. Approaching or attempting to play or swim with them may alter their behavior and their ability to fend for themselves in the wild. If you encounter a seal while fishing, take a short break or change locations. Fish with a barbless circle hook to minimize hooking injuries. Enjoy from a distance and use binoculars and telephoto lenses to get the best views without disturbing the seals.

Hawaiian Monk Seal Myths and Facts

Myth 1: Seals only forage at night.

Fact: Seals feed both during the day and at night, although this varies depending on age and sex class.

Fact: Seals feed both during the day and at night, although this varies depending on age and sex class.

Monk seals as a whole do not appear to prefer feeding at specific times of the day. This misperception is derived from dietary and behavioral observations. Monk seal diet studies found that seals eat a mixture of diurnal and nocturnal species. Though seals are consuming nocturnal species, they are not necessarily consuming them only at night. Nocturnal prey, such as eels and cephalopods, like to hide in crevices and rocks during the day, and footage from seal-born video cameras (crittercams) show seals probing and overturning rocks to flush and capture prey. Observations of seals on the beaches showed that the highest number ashore were mid-day with fewer animals in the morning and early evening, leading to the assumption that seals were primarily nocturnal foragers. However, new technology such as dive recorders and satellite tags are showing no significant difference between day and night feedings.

Myth 2: Seals eat too much of the fish targeted by fishermen. This poses a problem if the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) seal population grows.

Fact: Considering what science tells us about monk seal foraging, the overall impact of seals on fishing in Hawaii (recreational, subsistence, and commercial) is small.

Fact: Considering what science tells us about monk seal foraging, the overall impact of seals on fishing in Hawaii (recreational, subsistence, and commercial) is small.

The potential impact of seals on fishing in Hawaii is influenced by several factors:

There are a small number of seals in the MHI (~300 seals) – Seals consume a wide variety of marine organisms (not just fish), and many are species not targeted by fishers

Seals forage over wide areas, including habitats and depths not targeted by fishers – Even as the MHI seal population may grow naturally, their impacts on fisheries are expected to be very small as the overall MHI population will still be relatively small.

However, there could be impacts to individual fishermen when seals interact with their gear or catch. Guidelines have been developed to minimize these impacts. Review NOAA’s fisheries interactions guidelines for more information on how to avoid seal interactions.

Myth 3: Monk seals eat 400 pounds of fish per seal per day. Or, monk seals eat their weight in fish every day.

Fact: This is impossible. No large carnivore (meat eating animal) consumes the equivalent of its body weight in a day.

Fact: This is impossible. No large carnivore (meat eating animal) consumes the equivalent of its body weight in a day.

Very small animals, like shrews, hummingbirds, and some insects, etc., must consume large amounts of food relative to their size, but not marine mammals, including monk seals. Given the size of the monk seals stomach (only slightly larger than our own) it is actually impossible for monk seals to consume and digest that quantity of food.

Monk seals eat about 4-8% of their body weight, depending on the age class of the seal. If there is an increasing population of seals in the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) there is concern that seals may be negatively impacting the local ecosystem. A recent study estimated that a MHI seal consumes about 6.8 kilograms (15 pounds) of fish per day, which is only 0.009% of estimated available prey biomass. With 7,622 square kilometers (2,943 square miles) of foraging habitat in the MHI and an estimated monk seal population size of 300, this translates to a total consumption rate of about 0.45 kilograms (1 pound) of fish per square mile per day per seal.

Myth 4: Seals damage coral reefs as they hunt for food and thus damage fish habitat. This will get worse if the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) population.

Fact: Seals rarely damage live coral while they forage – they do sometimes lift or turn over rocks and root around in rubble and sand, but this material is not live coral, and this activity does not damage the ecosystem nor reduce the productivity of the fishery.

Fact: Seals rarely damage live coral while they forage – they do sometimes lift or turn over rocks and root around in rubble and sand, but this material is not live coral, and this activity does not damage the ecosystem nor reduce the productivity of the fishery.

There is no evidence, including many of hours of footage from seal-mounted video cameras, indicating that monk seals damage coral reefs.

Myth 5: Seals will attract sharks, which will put people at risk of shark attacks.

Fact: All information to date indicates that more monk seals in the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) has not, and will not, lead to more shark attacks on humans.

Fact: All information to date indicates that more monk seals in the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) has not, and will not, lead to more shark attacks on humans.

While the monk seal population has increased in the MHI over the past 10 years, incidents of shark attacks on people have shown no corresponding increase. According to the International Shark Attack File, there have been a total of only 136 documented shark attacks on people in Hawaii from 1828-2014, and 9 of these were fatal. From 2001-2014, the yearly number of attacks on humans in Hawaii showed no clear upward trend of shark attacks.

Tiger sharks are responsible for most shark attacks on humans in Hawaii, and tiger sharks also attack monk seals. However, only a small fraction of seals in the MHI have scars or new injuries from shark bites. Some studies have documented more white shark attacks on people (especially surfers) near seal colonies (for example, in California and South Africa). These colonies typically involve predictable and seasonal aggregations of tens of thousands of seals, and white sharks focus on these areas when seals are present. In contrast, there are presently around 300 seals in the MHI. These seals are scattered throughout the islands and do not aggregate in dense colonies. These small numbers mean that monk seals cannot be a significant source of food for sharks, because there are not nearly enough seals to sustain the sharks. A similar concern is often heard about the abundance of green turtles and shark attacks in Hawaii. However, despite the fact that green turtle abundance has been growing in Hawaii for decades, there has been no apparent increase in shark attacks on humans during this time.

Myth 6: Seals are a human safety risk because they will attack people.

Fact: Most monk seals are not aggressive toward people, unless they feel threatened (such as when a person gets between a mother seal and her pup).

Fact: Most monk seals are not aggressive toward people, unless they feel threatened (such as when a person gets between a mother seal and her pup).

Some seals that have been fed (intentionally or unintentionally) or those that have been interacted with (“played with”) by people may become dangerous when they grow up to be large, mature seals that persistently seek out human interaction.

Normal “wild” monk seals almost never attack or seek interactions with humans. There have been only a few known cases of aggressive interactions between seals and people. These have occurred either when a person has gotten too close to a protective mother’s pup or when a seal has become conditioned to associate humans with food or socialization and later became too “rough” with unsuspecting swimmers or divers.

Myth 7: Monk seals are not from Hawaii and they are being brought in by government agencies.

Fact: Monk seals are native to both the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI).

Fact: Monk seals are native to both the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI).

All evidence indicates that Hawaiian monk seals are endemic to the Hawaiian Islands, meaning they are only found in Hawaii and nowhere else in the world.

There are documented reports of monk seals sighted in the MHI going back to the 1800s, and archeological remains of monk seals dating to 1400-1700 AD were found on the Island of Hawaii. The Hawaiian monk seal likely reached the Pacific Ocean through the Central American Seaway (now blocked by the Isthmus of Panama) between 3 and 11 million years ago. There is no fossil or reported evidence of Hawaiian monk seals anywhere else in the world, except for in the Hawaiian Archipelago.

Although not as prominent in Native Hawaiian culture as other sea creatures, like sea turtles, recent research reveals that some Hawaiian families have traditional ties to monk seals and there are historical Hawaiian cultural references to monk seals. Many people have not seen or heard much about monk seals in the MHI in the past few generations because they have only recently become more numerous again in the MHI after being hunted to near extension in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The MHI seal population has naturally increased because of better reproductive success of the seals already here, not because seals are moving here from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI).

Myth 8: The seal population in the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) will explode like other invasive species (e.g., taʻape).

Fact: Many introduced species have indeed become problematic invasive species in Hawaii. However, monk seals are not an alien species and the biology of slow growing native monk seals (a marine mammal) is very different than the biology of Hawaii’s alien species (fish, plants, and land mammals).

Fact: Many introduced species have indeed become problematic invasive species in Hawaii. However, monk seals are not an alien species and the biology of slow growing native monk seals (a marine mammal) is very different than the biology of Hawaii’s alien species (fish, plants, and land mammals).

Monk seals are not an alien species in Hawaii (see Myth 8 above), so they do not have the ecological advantage that some alien species, such as taʻape or mongoose, have when they are introduced into new ecosystems. Female seals, on average, have less than one pup per year, compared to the thousands of offspring produced by alien fish species like taʻape, and the 6 or more offspring per year produced by a small land mammal, like a mongoose. Even among all types of pinnipeds (seals and sea lions), all of which are relatively slow reproducing species, the monk seal population appears to be among the slowest growing, even when conditions are favorable for population growth. This may be partly because Hawaii’s subtropical marine ecosystem is much less productive than the temperate and arctic ecosystems where the other pinnipeds live. Contrary to what it may seem, coral reef ecosystems have very low levels of nutrients in the water – that’s why the water is so clear. Temperate and arctic ecosystems, on the other hand, have relatively high nutrient levels and thus can support higher biological production and higher populations of pinnipeds.

Based on the best information available, it is believed that the monk seal population in the MHI is currently neither growing or falling. Based on sophisticated computer-based modeling to estimate future populations, it is thought that due to natural “saturation rates” and the current population size, it is predicted that the number of Hawaiian monk seals in the MHI could reach approximately 500 to 600 animals by the year 2030 - still a very low number considering the size, extent and complexity of the shoreline ecosystem.

“One way to open your eyes is to ask yourself, “What if I had never seen this before? What if I knew I would never see it again?” – Rachel Carson (Biologist, writer, ecologist, 1907-1964)

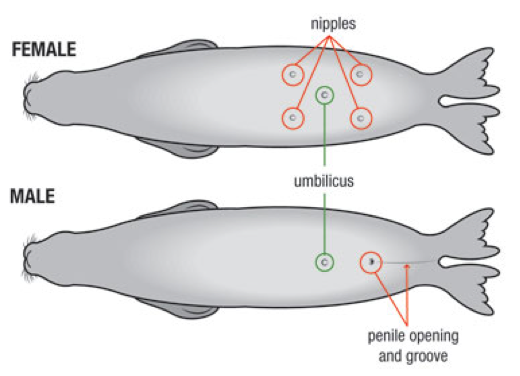

What Sex Is That Seal?

Other than DNA testing, the only way to confirm whether a seal is female or male is by looking at its belly.