How To Tell The Difference Between a Green and Hawksbill Sea Turtle

|

Common name: Green Sea Turtle Hawaiian name: Honu Latin name: Chelonia mydas Status: Protected & Threatened |

|

Common name: Hawksbill Turtle Hawaiian name: ‘Ea Latin name: Eretmochelys imbricata Status: Protected & Endangered |

Comparison of the Green turtle and the Hawksbill turtle:

|

Green Turtle

|

Hawksbill Turtle

|

|

|

Hawaiian Name

|

Honu

|

‘Ea

|

|

Status

|

Threatened

|

Endangered

|

|

Distribution

|

Common

|

Not common, mostly Maui and Big Island

|

|

Adult Weight

|

Up to 500 lbs.

|

Up to 200 lbs.

|

|

Adult Shell Length

|

3-4 ft.

|

2-3 ft.

|

|

Diving Depth

|

Up to 1500 ft.

|

Up to 1500 ft.

|

|

Breathing Cycle

|

Resting up to 3 hours

Normal – every 15 to 30 mins.

|

Up to 3 hours

Normal – every 15 to 30 mins.

|

|

Diet

|

Limu, seagrass and invertebrates

|

Sponges, algae & invertebrates

|

|

Sexual Maturity

|

25-35 years

|

20-29 years

|

|

Lifespan

|

80-100 years

|

30-50 years

|

|

Hawaii Nesting Activity

|

500-800 per year

|

20-25 per year

|

|

Basking

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Carapace (Shell)

|

High domed

Non-overlapping scutes

Smooth edge

Olive to black color

|

Flatter, more colorful

Overlapping scutes

Jagged edge

More colorful

|

|

Claws

|

1 per flipper

|

2 per flipper

|

|

Nesting Frequency

|

2 to 8 years

|

4 years

|

|

Intervals of Nesting

|

4 nests / 14 days apart

|

1 to 6 nests / 20 days apart

|

|

Eggs/Clutch & Incubation

|

~100 eggs / ~2 months

|

~180 eggs / ~2 months

|

Frequently Asked Questions ( FAQ )

Q. There’s a monk seal on the beach and it looks sick – what should I do?

Q. There’s a monk seal on the beach and it looks sick – what should I do?

A. Most seals that haul-out on the shoreline are just fine. They may have mucus around their eyes, scars on their body, and may lie very still, as if they are not breathing, but that’s normal. Please keep your distance; do not try to get close to the animal. Please stay behind any signs or ropes erected by Hawaii Marine Animal Response (HMAR) or other authorized personnel. If there are HMAR, law enforcement or other NOAA-sanctioned personnel on scene (identifiable by uniform or ID), please follow their instructions and recommendations for safe and responsible viewing. Hawaiian monk seals need to be allowed to rest undisturbed. Please report all sightings of monk seals by calling our 24-hour toll-free hotline at 1-888-256-9840.

Q. There’s a whale or dolphin on the beach or swimming in very shallow water – what should I do?

A. Whales and dolphins on the shoreline or swimming in very shallow water (less than 5 feet) are usually sick or injured. Please keep your distance – these animals are very strong, heavy, and unpredictable – and call our 24-hour toll-free hotline at 1-888-256-9840.

Q. I see a marine mammal that’s entangled in string, rope or net – what should I do?

A. Call the 24-hour toll-free hotline at 1-888-256-9840. If it’s safe, please stay nearby the animal to keep track of it until trained responders can arrive. Never try to untangle a marine mammal on your own, without permission and guidance from NOAA. Too many well-meaning people have been seriously injured or drowned while attempting to save an entangled whale, dolphin or seal.

Q. What should I do if I accidentally hook a monk seal while fishing or if I see a hooked seal?

A. Please immediately call our 24-hour toll-free hotline at 1-888-256-9840. You may make your report anonymously. You will then be given guidance over the phone on what to do depending on the situation. Review NOAA’s fisheries interactions guidelines for more information on how to avoid seal interactions.

Q. Why should we protect Hawaiian monk seals? They don’t belong in the main Hawaiian Islands and eat all our fish!

A. Hawaiian monk seals are native to the Hawaiian Islands, and occur nowhere else in the world. See Hawaiian Monk Seal Myths and Facts. There is good archaeological evidence that monk seals were here before the first humans arrived in the Hawaiian Islands. Seals usually feed on bottom-dwelling creatures, such as eels, flatfish, wrasses, octopus, and crustaceans. Seals have never been observed hunting pelagic fish, such as mahi-mahi, ahi, aku, etc. Like sharks and other marine predators, seals play an essential role in our reef ecosystem, maintaining a balance that allows for the highest levels of productivity in our local fisheries.

Q. How close can I get to monk seals?

A. There is no law specifying the minimum distance people can approach a monk seal, however, getting close to these animals may constitute a violation of federal or state law if the animal is disturbed or if your action has the potential to intentionally disturb its natural behavior. If Hawaii Marine Animal Response (HMAR), law enforcement or other NOAA-sanctioned personnel are on scene (identifiable by uniform or ID), please follow their instructions and recommendations for safe and responsible viewing. Please stay behind any signs or ropes that have been erected by HMAR or other authorized personnel. They are there for your safety, to minimize animal interaction and for your awareness. If no signs, ropes or authorized personnel are in the vicinity, it is recommended that you stay at least 50 feet from Hawaiian monk seals and 150 feet if you encounter a mother monk seal with a pup. Pets, especially dogs, can pose a risk to monk seals. Please keep them on a leash when in the presence of monk seals to avoid injury or disease transmission for both seals and pets. In the ocean, monk seals may exhibit inquisitive behavior. Approaching or attempting to play or swim with them may alter their behavior and their ability to fend for themselves in the wild. If you encounter a seal while fishing, take a short break or change locations. Fish with a barbless circle hook to minimize hooking injuries. Enjoy from a distance and use binoculars and telephoto lenses to get the best views without disturbing the seals.

Hawaiian Monk Seal Myths and Facts

Myth 1: Seals only forage at night.

Fact: Seals feed both during the day and at night, although this varies depending on age and sex class.

Fact: Seals feed both during the day and at night, although this varies depending on age and sex class.

Monk seals as a whole do not appear to prefer feeding at specific times of the day. This misperception is derived from dietary and behavioral observations. Monk seal diet studies found that seals eat a mixture of diurnal and nocturnal species. Though seals are consuming nocturnal species, they are not necessarily consuming them only at night. Nocturnal prey, such as eels and cephalopods, like to hide in crevices and rocks during the day, and footage from seal-born video cameras (crittercams) show seals probing and overturning rocks to flush and capture prey. Observations of seals on the beaches showed that the highest number ashore were mid-day with fewer animals in the morning and early evening, leading to the assumption that seals were primarily nocturnal foragers. However, new technology such as dive recorders and satellite tags are showing no significant difference between day and night feedings.

Myth 2: Seals eat too much of the fish targeted by fishermen. This poses a problem if the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) seal population grows.

Fact: Considering what science tells us about monk seal foraging, the overall impact of seals on fishing in Hawaii (recreational, subsistence, and commercial) is small.

Fact: Considering what science tells us about monk seal foraging, the overall impact of seals on fishing in Hawaii (recreational, subsistence, and commercial) is small.

The potential impact of seals on fishing in Hawaii is influenced by several factors:

There are a small number of seals in the MHI (~300 seals) – Seals consume a wide variety of marine organisms (not just fish), and many are species not targeted by fishers

Seals forage over wide areas, including habitats and depths not targeted by fishers – Even as the MHI seal population may grow naturally, their impacts on fisheries are expected to be very small as the overall MHI population will still be relatively small.

However, there could be impacts to individual fishermen when seals interact with their gear or catch. Guidelines have been developed to minimize these impacts. Review NOAA’s fisheries interactions guidelines for more information on how to avoid seal interactions.

Myth 3: Monk seals eat 400 pounds of fish per seal per day. Or, monk seals eat their weight in fish every day.

Fact: This is impossible. No large carnivore (meat eating animal) consumes the equivalent of its body weight in a day.

Fact: This is impossible. No large carnivore (meat eating animal) consumes the equivalent of its body weight in a day.

Very small animals, like shrews, hummingbirds, and some insects, etc., must consume large amounts of food relative to their size, but not marine mammals, including monk seals. Given the size of the monk seals stomach (only slightly larger than our own) it is actually impossible for monk seals to consume and digest that quantity of food.

Monk seals eat about 4-8% of their body weight, depending on the age class of the seal. If there is an increasing population of seals in the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) there is concern that seals may be negatively impacting the local ecosystem. A recent study estimated that a MHI seal consumes about 6.8 kilograms (15 pounds) of fish per day, which is only 0.009% of estimated available prey biomass. With 7,622 square kilometers (2,943 square miles) of foraging habitat in the MHI and an estimated monk seal population size of 300, this translates to a total consumption rate of about 0.45 kilograms (1 pound) of fish per square mile per day per seal.

Myth 4: Seals damage coral reefs as they hunt for food and thus damage fish habitat. This will get worse if the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) population.

Fact: Seals rarely damage live coral while they forage – they do sometimes lift or turn over rocks and root around in rubble and sand, but this material is not live coral, and this activity does not damage the ecosystem nor reduce the productivity of the fishery.

Fact: Seals rarely damage live coral while they forage – they do sometimes lift or turn over rocks and root around in rubble and sand, but this material is not live coral, and this activity does not damage the ecosystem nor reduce the productivity of the fishery.

There is no evidence, including many of hours of footage from seal-mounted video cameras, indicating that monk seals damage coral reefs.

Myth 5: Seals will attract sharks, which will put people at risk of shark attacks.

Fact: All information to date indicates that more monk seals in the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) has not, and will not, lead to more shark attacks on humans.

Fact: All information to date indicates that more monk seals in the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) has not, and will not, lead to more shark attacks on humans.

While the monk seal population has increased in the MHI over the past 10 years, incidents of shark attacks on people have shown no corresponding increase. According to the International Shark Attack File, there have been a total of only 136 documented shark attacks on people in Hawaii from 1828-2014, and 9 of these were fatal. From 2001-2014, the yearly number of attacks on humans in Hawaii showed no clear upward trend of shark attacks.

Tiger sharks are responsible for most shark attacks on humans in Hawaii, and tiger sharks also attack monk seals. However, only a small fraction of seals in the MHI have scars or new injuries from shark bites. Some studies have documented more white shark attacks on people (especially surfers) near seal colonies (for example, in California and South Africa). These colonies typically involve predictable and seasonal aggregations of tens of thousands of seals, and white sharks focus on these areas when seals are present. In contrast, there are presently around 300 seals in the MHI. These seals are scattered throughout the islands and do not aggregate in dense colonies. These small numbers mean that monk seals cannot be a significant source of food for sharks, because there are not nearly enough seals to sustain the sharks. A similar concern is often heard about the abundance of green turtles and shark attacks in Hawaii. However, despite the fact that green turtle abundance has been growing in Hawaii for decades, there has been no apparent increase in shark attacks on humans during this time.

Myth 6: Seals are a human safety risk because they will attack people.

Fact: Most monk seals are not aggressive toward people, unless they feel threatened (such as when a person gets between a mother seal and her pup).

Fact: Most monk seals are not aggressive toward people, unless they feel threatened (such as when a person gets between a mother seal and her pup).

Some seals that have been fed (intentionally or unintentionally) or those that have been interacted with (“played with”) by people may become dangerous when they grow up to be large, mature seals that persistently seek out human interaction.

Normal “wild” monk seals almost never attack or seek interactions with humans. There have been only a few known cases of aggressive interactions between seals and people. These have occurred either when a person has gotten too close to a protective mother’s pup or when a seal has become conditioned to associate humans with food or socialization and later became too “rough” with unsuspecting swimmers or divers.

Myth 7: Monk seals are not from Hawaii and they are being brought in by government agencies.

Fact: Monk seals are native to both the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI).

Fact: Monk seals are native to both the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI).

All evidence indicates that Hawaiian monk seals are endemic to the Hawaiian Islands, meaning they are only found in Hawaii and nowhere else in the world.

There are documented reports of monk seals sighted in the MHI going back to the 1800s, and archeological remains of monk seals dating to 1400-1700 AD were found on the Island of Hawaii. The Hawaiian monk seal likely reached the Pacific Ocean through the Central American Seaway (now blocked by the Isthmus of Panama) between 3 and 11 million years ago. There is no fossil or reported evidence of Hawaiian monk seals anywhere else in the world, except for in the Hawaiian Archipelago.

Although not as prominent in Native Hawaiian culture as other sea creatures, like sea turtles, recent research reveals that some Hawaiian families have traditional ties to monk seals and there are historical Hawaiian cultural references to monk seals. Many people have not seen or heard much about monk seals in the MHI in the past few generations because they have only recently become more numerous again in the MHI after being hunted to near extension in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The MHI seal population has naturally increased because of better reproductive success of the seals already here, not because seals are moving here from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI).

Myth 8: The seal population in the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) will explode like other invasive species (e.g., taʻape).

Fact: Many introduced species have indeed become problematic invasive species in Hawaii. However, monk seals are not an alien species and the biology of slow growing native monk seals (a marine mammal) is very different than the biology of Hawaii’s alien species (fish, plants, and land mammals).

Fact: Many introduced species have indeed become problematic invasive species in Hawaii. However, monk seals are not an alien species and the biology of slow growing native monk seals (a marine mammal) is very different than the biology of Hawaii’s alien species (fish, plants, and land mammals).

Monk seals are not an alien species in Hawaii (see Myth 8 above), so they do not have the ecological advantage that some alien species, such as taʻape or mongoose, have when they are introduced into new ecosystems. Female seals, on average, have less than one pup per year, compared to the thousands of offspring produced by alien fish species like taʻape, and the 6 or more offspring per year produced by a small land mammal, like a mongoose. Even among all types of pinnipeds (seals and sea lions), all of which are relatively slow reproducing species, the monk seal population appears to be among the slowest growing, even when conditions are favorable for population growth. This may be partly because Hawaii’s subtropical marine ecosystem is much less productive than the temperate and arctic ecosystems where the other pinnipeds live. Contrary to what it may seem, coral reef ecosystems have very low levels of nutrients in the water – that’s why the water is so clear. Temperate and arctic ecosystems, on the other hand, have relatively high nutrient levels and thus can support higher biological production and higher populations of pinnipeds.

Based on the best information available, it is believed that the monk seal population in the MHI is currently neither growing or falling. Based on sophisticated computer-based modeling to estimate future populations, it is thought that due to natural “saturation rates” and the current population size, it is predicted that the number of Hawaiian monk seals in the MHI could reach approximately 500 to 600 animals by the year 2030 - still a very low number considering the size, extent and complexity of the shoreline ecosystem.

“One way to open your eyes is to ask yourself, “What if I had never seen this before? What if I knew I would never see it again?” – Rachel Carson (Biologist, writer, ecologist, 1907-1964)

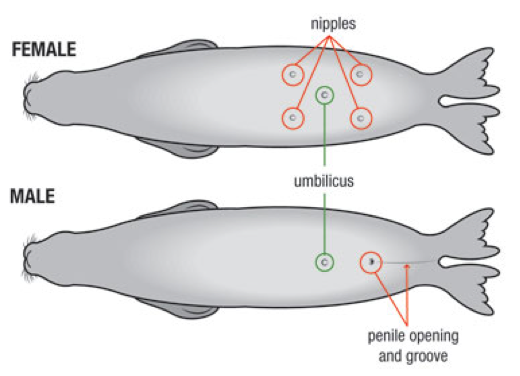

What Sex Is That Seal?

Other than DNA testing, the only way to confirm whether a seal is female or male is by looking at its belly.

How to Tell Seals Apart

Most Hawaiian monk seals have unique natural markings, such as scars or natural bleach marks, that help identify individual seals. Many seals have identifiers such as flipper tags or letters and numbers applied to the animal’s fur with bleach.

|

|

|

| Example of a Hawaiian monk seal with a natural round bleach mark on its right side | Example of hind flipper tags | Example of a monk seal with letters and numbers applied to the animal’s fur with bleach. |

Why is the Hawaiian Monk Seal Endangered?

The Hawaiian monk seal is an endangered marine mammal that inhabits, and is endemic to, the Hawaiian Islands. Despite decades long multi-disciplinary research and recovery tactics, the future survival of this species is still tenuous with between 1,350 and 1,400 individuals remaining at the end of 2017.

The Hawaiian monk seal is an endangered marine mammal that inhabits, and is endemic to, the Hawaiian Islands. Despite decades long multi-disciplinary research and recovery tactics, the future survival of this species is still tenuous with between 1,350 and 1,400 individuals remaining at the end of 2017.

The species is divided into two primary sub-populations. One sub-population that inhabits the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI), and another sub-population that inhabits the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) of Niihau, Kauai, Oahu, Molokai, Maui, Lanai, Kahoolawe and Hawaii Island.

The sub-population of seals in the NWHI has generally suffered from annual declines for decades due to several natural and potentially human-related causes, some of which have not, as-yet, been fully understood. However, in the past few years there has been a very small percentage increase of the population. The difficulty of studying and impacting the sub-population in the NWHI is exacerbated by the extreme remoteness of these islands and the complicated logistics and costs of mounting scientific field expeditions to the area.

The sub-population of seals in the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) is currently static (neither growing or falling), however, generally the MHI provides for good seal survival rates, more abundant food sources and other positive environmental conditions. This population in the MHI represents an important opportunity for us to save this species and is therefore the primary focus of our work.

The key challenges to species protection & recovery include:

Human-seal interaction. Inappropriate human-seal interaction can negatively impact pupping behavior and pup survival, can disrupt needed monk seal rest cycles, can lead to conditioning seals to human presence posing a danger to both seals and humans, and can expose seals to attacks from pets and their related injuries, disease and death. Unfortunately, there have also been multiple cases of violence and fatal attacks upon monk seals by humans.

For your safety and the animals’ stewardship, please give them space when seen on the shoreline. If Hawaii Marine Animal Response (HMAR), law enforcement or other NOAA-sanctioned personnel (identifiable by uniform or ID) are on scene when an animal is present, please follow their instructions and recommendations for safe and responsible viewing of the animals. Please stay behind any signs or ropes that may have been erected by HMAR, law enforcement or other NOAA-authorized personnel. If no authorized personnel, or signs and ropes are present, it is recommended that you stay at least 50 feet from monk seals, 150 feet if you encounter a seal mom with a pup. Pets, especially dogs, can pose a risk to monk seals. Please keep them on a leash when in the presence of monk seals to avoid injury or disease transmission for both seals and pets. In the ocean, monk seals may exhibit inquisitive behavior. Approaching or attempting to play or swim with them may alter their behavior and their ability to fend for themselves in the wild. Attempting to interact with, swim with or play with seals in the water can be dangerous. Enjoy monk seals from a distance and use binoculars and telephoto lenses to get the best views without disturbing the seals.

Fishery and monk seal interactions include hookings on fishing gear and entanglement in fishing nets, both of which can lead to monk seal injury or death. Review NOAA’s fisheries interactions guidelines for more information on how to avoid seal interactions.

Exposure to parasitic and viral diseases. The Hawaiian monk seal is susceptible to several diseases that could lead to widespread seal deaths. For example, an outbreak of Phocine distemper virus (PDV) in 1988 caused the death of over 10,000 harbor seals in northern Europe. In the same year, two more outbreaks of viral disease in aquatic mammals occurred, one in Lake Baikal, Siberia, the other in waters near Britain and the Netherlands. Then in 2002, another morbillivirus epidemic in the North Sea killed over 21,000 seals. A disease outbreak such as this in the Hawaiian monk seal population could result in many seal deaths and weaken the species to the extent it may be unable to recover. In recent years Toxoplasmosis and Leptospirosis have killed numerous Hawaiian monk seals and viruses in the morbillivirus family also pose very dangerous threats to our population.

Habitat threats. Changes in, or damage to monk seal habitat are contributing to the danger posed to the species. These habitat threats include coastal development and sea level rise, which are shrinking the critical habitat areas needed by monk seals for rest and pupping activity. Since these seals spend approximately 1/3 of their time on land, preserving beaches and other coastal areas where seals can haul out is critical. In addition, inland water runoff can become dangerous pathways for Toxoplasma gondii and Leptospira spp. (see “Exposure to Diseases” above), both of which cause diseases that can be fatal to Hawaiian monk seals.

Public understanding and support for the Hawaiian monk seal. Many people living in or visiting the Hawaiian Islands are either ambivalent to, or have no knowledge of the Hawaiian monk seal due to the small number of seals or a lack of exposure to the animals during recent history. There is also a percentage of the human population that has negative views of the seals due to misinformation or a misunderstanding of Hawaiian monk seals, their behaviors and their habitat. Education and outreach, which positively changes public attitudes and behaviors, can reduce damaging human and fishery interactions.

Field response, educational and outreach capacity. Due to competing government priorities, federal and state agencies charged with the support of Hawaiian monk seal field response, education and community outreach activities, have insufficient funding to mount all of the work and activity needed. Therefore, public and private funding for nonprofits that can provide the work to fill this void can positively impact the other key challenges listed above for saving the Hawaiian monk seal.